Deep within the mythical Himavanta forest of Thai Buddhist tradition grows a tree unlike any other: the Nariphon. Bearing fruit in the exact likeness of beautiful young women, this legendary flora has captivated the artistic and spiritual imagination of Southeast Asia for centuries. But where does this striking and complex iconography originate? In this first instalment of our two-part series, we trace the roots of the fruit-maiden from its ancient South Asian origins to its profound assimilation into Thai cosmology, revealing how a botanical myth transforms into a mechanism of divine protection and a profound lesson on impermanence.

Tree Iconography

From Nāri-lāta to Nariphon: Examining the Iconographic Journey of Fruit-Maiden Symbolism in Thai Art

Arcangelo Di Paolo (M.Phil.)

February 21, 2026

The Roots of the Myth: The Nāri-lāta Connection

The journey of the fruit-maiden motif does not begin in Thailand, but rather in the broader cultural and religious milieu of South Asia. To fully understand the Nariphon (Thai: นารีผล), one must first examine its iconographic ancestor: the Nāri-lāta (or Nārilatā-wela).

In ancient South Asian lore, particularly within Sri Lankan and Indian mythological texts, the Nāri-lāta is described as a miraculous vine or climbing plant that blooms with flowers resembling women of peerless beauty. These botanical maidens were often depicted as profound distractions for ascetics and hermits meditating in the deep forests.

As maritime trade networks, artistic exchanges, and Buddhist texts traversed the Indian Ocean, brought by the monsoon winds, this compelling visual metaphor travelled with them. It found highly fertile ground in the religious landscape of Southeast Asia. However, when the motif arrived in what is now Thailand, it was not merely copied; it was entirely recontextualised. The creeping vine of South Asia was elevated into a monumental tree, adapted to serve the specific narrative and architectural needs of Thai Theravada Buddhism.

Divine Protection and the Vessantara Jātaka

The most prominent narrative anchoring the Nariphon in Thai culture is its integral connection to the Vessantara Jātaka, the beloved tale of the Buddha's penultimate earthly incarnation as a profoundly generous prince.

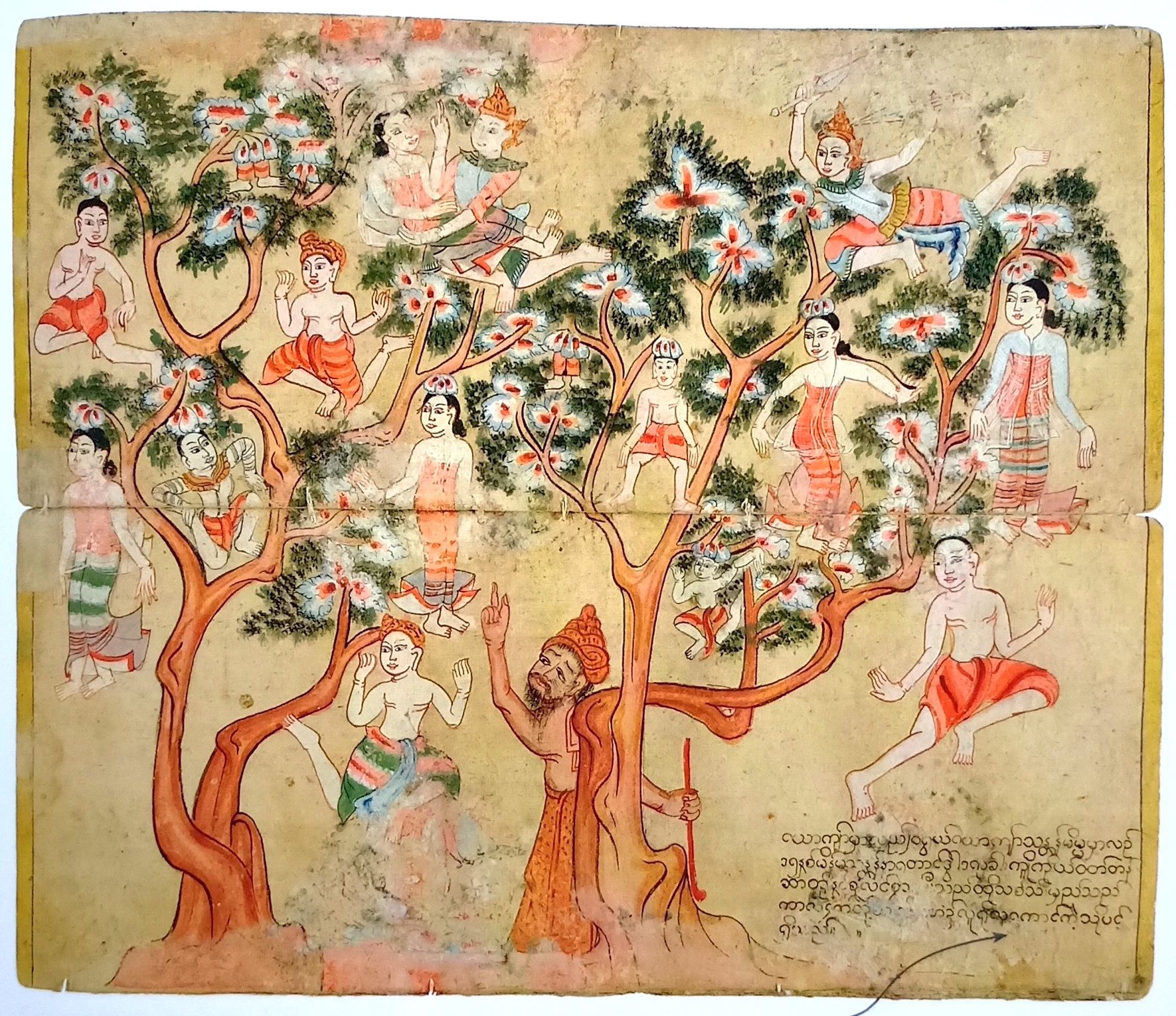

According to the legend, Prince Vessantara, his wife Matsi (Maddi), and their children were exiled to the wild Himavanta forest. Matsi, a woman of unparalleled grace and beauty, would frequently venture deep into the forest to gather wild fruits and roots for her family. The forest, however, was teeming with Vidyadharas and ascetics who, despite their rigorous meditative practices, had not yet conquered their earthly lusts and desires.

To protect Matsi from being accosted or harmed by these magically endowed hermits, the god Indra (Sakka) intervened. He miraculously created a grove of sixteen Nariphon trees, strategically placed at the boundaries of Vessantara’s hermitage.

Inscription: "The maiden fruit (thu-yong-thee ) tree is rare and grows wild in the deep, remote areas of Himavanta. It bears fruit resembling the shape of human beings. The male fruit is a boy of 20 years and the female fruit has the beauty and shape of a 15-year-old girl. All are well clothed and when they ripen they fall to the ground and are eaten by birds leaving only an inner core which resembles a human skeleton."

Divine Protection and the Vessantara Jātaka

The most prominent narrative anchoring the Nariphon in Thai culture is its integral connection to the Vessantara Jātaka, the beloved tale of the Buddha's penultimate earthly incarnation as a profoundly generous prince.

According to the legend, Prince Vessantara, his wife Matsi (Maddi), and their children were exiled to the wild Himavanta forest. Matsi, a woman of unparalleled grace and beauty, would frequently venture deep into the forest to gather wild fruits and roots for her family. The forest, however, was teeming with Vidyadharas and ascetics who, despite their rigorous meditative practices, had not yet conquered their earthly lusts and desires.

To protect Matsi from being accosted or harmed by these magically endowed hermits, the god Indra (Sakka) intervened. He miraculously created a grove of sixteen Nariphon trees, strategically placed at the boundaries of Vessantara’s hermitage.

Temple murals frequently depict the chaotic mid-air battles of the Vidyadharas, fighting desperately over the Nariphon maidens, illustrating the destructive nature of unchecked desire.

The Biology of the Myth: Temptation and Impermanence

The physical description of the Nariphon in Thai lore is remarkably specific and visually striking. The trees bore fruit identical in form, touch, and scent to beautiful sixteen-year-old girls. Notably, the iconographic tradition dictates that these fruit-maidens are attached to the branches of the tree by their heads, hanging suspended in the forest canopy.

When the lustful Vidyadharas and ascetics caught sight of these extraordinary fruits, their meditative discipline shattered. The myth describes fierce, often violent battles erupting amongst the sorcerers, fighting in mid-air to claim the fruit-maidens for themselves.

Once plucked, the ascetics would engage in amorous relations with the fruit. However, this divine intervention carried a harsh spiritual penalty. The fruit would sustain the hermit for exactly seven days, after which it would rapidly wither and rot away—a visceral, botanical lesson in the core Buddhist concept of Anicca (impermanence). Furthermore, the act of succumbing to their desires caused the ascetics to instantly lose their magical flying abilities and meditative powers (Jhana) for four months.

The 'Taboo Software' of the Sacred Forest

In this context, the Nariphon acts as a form of "spiritual software" or a divine trap. It regulates behaviour within the sacred forest, serving simultaneously as a rigorous test of ascetic discipline and an infallible protective barrier for the virtuous Matsi.

By contextualising the tree within the Vessantara Jātaka, Thai artisans and theologians elevated the fruit-maiden. She is not merely a passive object of beauty, but an active participant in the moral landscape of Buddhism—an arbiter of lust, a protector of virtue, and a profound symbol of the fleeting nature of worldly attachments.

Coming up in Part 2...

How did this rich mythological and theological narrative translate into physical art? In the second part of this series, we will examine the Iconographic Evolution and Modern Art, analysing how the Nariphon transitioned from classical temple murals to contemporary sculptures, amulets, and modern media.

- Read the Next Instalment: The Myth of the Nariphon in Thai Art: An Iconographic Journey (Part 2) (Link to be updated upon publication)

- Explore More: Discover more about the spiritual ecology of Asia in our article on Decoding Spiritual Architecture in the Annamite Mountains.

Download the Full Research Paper

For a complete, in-depth academic analysis of the Nāri-lāta to Nariphon transition, including extensive citations, structural analysis, and visual comparisons, you can access the original peer-reviewed publication by Arcangelo Di Paolo.

PAPER

Spatial Syntax of the Sacred Ficus

A. Di Paolo

January 12, 2026

PAPER

The Sentient Landscape: An Examination of Asia's Cosmological Vision of the Forest

A. Di Paolo

January 16, 2026

PAPER

An Eco-Dhammic Response: The Realignment of Soteriology and Conservation in Contemporary Thai Buddhism

A. Di Paolo

January 23, 2026