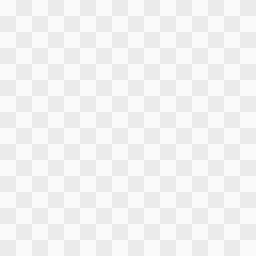

This paper argues that the traditional Asian vision of the forest, particularly within the Indonesian archipelago, is fundamentally cosmological rather than utilitarian. It advances the thesis that this worldview conceives of the landscape not as a passive object for extraction, but as a sentient social entity with which human communities must negotiate. The analysis begins by examining the spiritual foundations of this vision, focusing on the animistic concept of sacred places ( angker ) that function as zones of spiritual authority. It then presents a typology of sacred forests that arise from this worldview, including spiritually prohibited areas, cemetery forests, and aristocratic reserves. Subsequently, the paper details the traditional management practices—invisible social fences built on taboo and reverence—that translate belief into ecological function. The paper concludes by assessing the profound threats posed by a contrasting colonial and modern worldview, which reduces nature to an economic resource, while also noting how contemporary ecological science is increasingly validating the tangible ecosystem services that these ancient, culturally-grounded conservation models provide.

Sacred Forest | Indonesia

Invisible Social Fences: How Indigenous Taboos Outperform Colonial Forestry in Conserving Biodiversity

A. Di Paolo

January 16, 2026

Introduction: The Sentient Landscape

The global discourse on forest management has long been dominated by a Western paradigm rooted in resource economics and state-led scientific administration. The intellectual foundation of this model is a utilitarian categorization of nature, exemplified by the Dutch colonial distinction between commercially valuable teak and ecologically complex but economically "worthless" junglewood (Boomgaard, 1992). This paper advances a contrasting thesis: that the traditional vision of the forest in much of Asia is fundamentally cosmological, treating the landscape not as a factory for timber but as a sentient social entity. Within this framework, the forest is imbued with agency, spirits, and history, demanding social negotiation and reciprocity from human communities rather than submitting to purely economic logic.

This analysis will explore the depth and practical application of this cosmological vision, drawing primarily on historical evidence from the Indonesian archipelago. It will use the enduring concept of haunted or sacred places—known as angker in Java and keramat in Sumatra—as a central case study to illustrate how spiritual beliefs have historically regulated human-environment interactions with a high degree of efficacy (Boomgaard, 1999). By examining the spiritual foundations, management practices, and tangible ecosystem benefits of this worldview, this paper argues that these traditional systems represent a sophisticated and resilient form of ecological governance. It will also show, however, that these systems face severe threats from the imposition of a modern economic order, a conflict epitomized by the state-led deforestation driven by the Dutch East India Company (VOC). This investigation begins by exploring the core spiritual beliefs that animate this sentient landscape.

A Typology of Sacred Forests

Spiritual beliefs manifest physically on the landscape through the designation of distinct types of sacred and restricted-use areas. This classification system illustrates the practical application of the cosmological vision, moving from abstract belief to concrete land management. By categorizing these spaces, we can see how a shared worldview created a mosaic of protected lands, each serving different but often complementary conservational functions.

Spiritually Prohibited Areas and Cemetery Forests

The most potent form of traditional protection arises from direct spiritual prohibition, a form of social contract with the non-human world.

- Prohibited Areas: Sites designated as angker or keramat functioned as what can be described as "forbidden forests." Access was governed by powerful social taboos that prohibited nearly all forms of resource extraction. The rules were clear and culturally enforced: it was forbidden to harvest timber or collect fruit, and one could only enter such places "for devotional purposes and with the purest of intentions" (Boomgaard, 1999). These areas were, in essence, the strictest form of protected nature reserve, maintained not by fences and guards but by collective belief.

- Cemetery Forests: A specific and widespread subset of prohibited areas was linked to the veneration of ancestors. The sanctity of the dead extended to the landscape surrounding their final resting place, creating protected groves. This was not an isolated phenomenon. The Getas reserve in Central Java was culturally centered on an ancient Javanese graveyard long before its formal recognition by the colonial state, while the Pangandaran reserve on the Penanjung peninsula was similarly preserved due to the presence of old trees and an ancient tomb (Boomgaard, 1999).

Indigenous Royal and Aristocratic Reserves

Distinct from forests protected by spiritual taboo were those set aside by secular, aristocratic authority for the exclusive use of rulers. Javanese rulers established royal game reserves

( larangan ), while the aristocracy in Southwest Sulawesi maintained special hunting grounds ( ongko ). The primary purpose of these reserves was to provide a venue for elite hunting, particularly of deer and wild cattle ( banteng ). Intriguingly, it has been suggested that for Sulawesi, "it is possible that both the deer and the hunting technique...were imported from Java at an early stage," hinting at a broader cultural diffusion of elite land-use practices (Boomgaard, 1999, p. 260). These aristocratic reserves had a mixed conservational impact.

On one hand, they successfully preserved large tracts of forest cover from agricultural conversion. On the other, they were subject to exploitation by the very rulers who established them, with historical accounts of hunts where "hundreds of deer were killed," raising the possibility of localized over-hunting (Boomgaard, 1999). These different types of protected areas were all managed through a sophisticated set of culturally enforced rules.

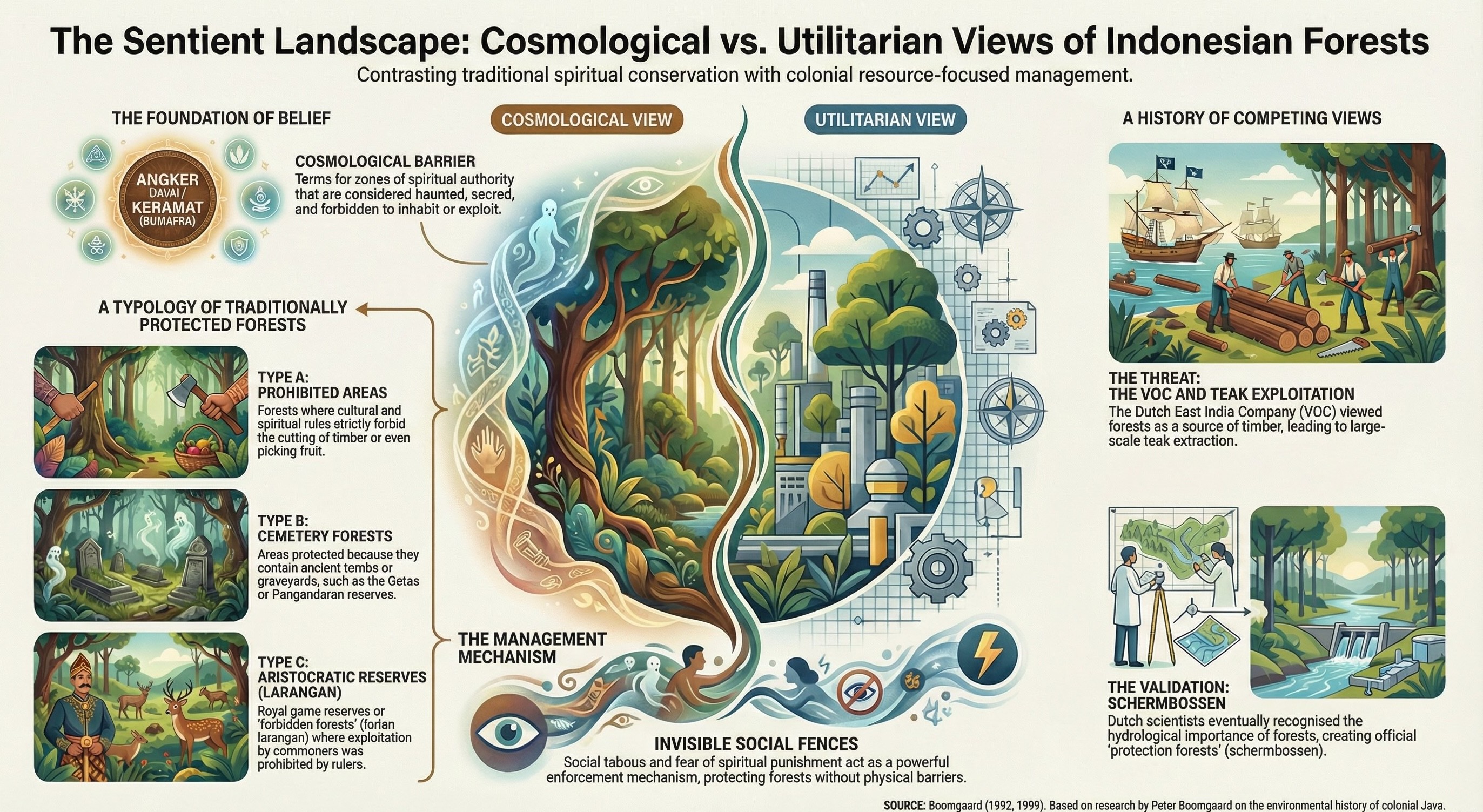

A Javanese man meditating under a Banyan tree. Dutch East Indies, before 1940 | Collectie Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen 1916

A Typology of Sacred Forests

Spiritual beliefs manifest physically on the landscape through the designation of distinct types of sacred and restricted-use areas. This classification system illustrates the practical application of the cosmological vision, moving from abstract belief to concrete land management. By categorizing these spaces, we can see how a shared worldview created a mosaic of protected lands, each serving different but often complementary conservational functions.

Spiritually Prohibited Areas and Cemetery Forests

The most potent form of traditional protection arises from direct spiritual prohibition, a form of social contract with the non-human world.

- Prohibited Areas: Sites designated as angker or keramat functioned as what can be described as "forbidden forests." Access was governed by powerful social taboos that prohibited nearly all forms of resource extraction. The rules were clear and culturally enforced: it was forbidden to harvest timber or collect fruit, and one could only enter such places "for devotional purposes and with the purest of intentions" (Boomgaard, 1999). These areas were, in essence, the strictest form of protected nature reserve, maintained not by fences and guards but by collective belief.

- Cemetery Forests: A specific and widespread subset of prohibited areas was linked to the veneration of ancestors. The sanctity of the dead extended to the landscape surrounding their final resting place, creating protected groves. This was not an isolated phenomenon. The Getas reserve in Central Java was culturally centered on an ancient Javanese graveyard long before its formal recognition by the colonial state, while the Pangandaran reserve on the Penanjung peninsula was similarly preserved due to the presence of old trees and an ancient tomb (Boomgaard, 1999).

Indigenous Royal and Aristocratic Reserves

Distinct from forests protected by spiritual taboo were those set aside by secular, aristocratic authority for the exclusive use of rulers. Javanese rulers established royal game reserves

( larangan ), while the aristocracy in Southwest Sulawesi maintained special hunting grounds ( ongko ). The primary purpose of these reserves was to provide a venue for elite hunting, particularly of deer and wild cattle ( banteng ). Intriguingly, it has been suggested that for Sulawesi, "it is possible that both the deer and the hunting technique...were imported from Java at an early stage," hinting at a broader cultural diffusion of elite land-use practices (Boomgaard, 1999, p. 260). These aristocratic reserves had a mixed conservational impact.

On one hand, they successfully preserved large tracts of forest cover from agricultural conversion. On the other, they were subject to exploitation by the very rulers who established them, with historical accounts of hunts where "hundreds of deer were killed," raising the possibility of localized over-hunting (Boomgaard, 1999). These different types of protected areas were all managed through a sophisticated set of culturally enforced rules.

These structures mark a hutan lindung (protected forest) or sacred grove, where spiritual boundaries dictate conservation. The placement of religious artifacts within the dense vegetation signifies a zone where the terrestrial and the divine intersect, protected not by fences, but by the reverence commanded by the site itself.

Traditional Management Practices

The practical efficacy of this cosmological vision is best understood by analysing its enforcement mechanisms, which operate not through state coercion but through a system of what can be termed "Invisible Social Fences." These culturally embedded rules and taboos perform the same function as modern conservation tools, but they rely on social cohesion, shared belief, and the expectation of spiritual consequence. This system represents a form of social negotiation with a sentient landscape, a stark contrast to the top-down, coercive enforcement of purely economic demands characteristic of the colonial state.

The Power of Customary Rules and Taboos

Traditional management was codified in both formal village by-laws and powerful informal taboos. In some late-nineteenth-century Javanese villages, for example, by-laws explicitly forbade the felling of trees on wooded commons to prevent deforestation, while others restricted felling rights to village inhabitants to prevent commercial exploitation by outsiders (Boomgaard, 1999). However, the most powerful management tool was the social taboo associated with angker places. This deeply ingrained cultural norm effectively prohibited resource extraction far more completely than any physical fence could.

The shared belief in the sacredness of a place and the potential for spiritual retribution for violating it was the ultimate enforcement mechanism.

Functional Equivalence to Modern Conservation

This analysis reveals a system where traditional rituals and taboos serve the same protective function as modern, science-based conservation methods. The cultural fear of spiritual punishment for desecrating an angker site is functionally equivalent to the legal penalties, such as fines or imprisonment, enforced by a modern park ranger. By creating zones where human activity is strictly limited by a shared moral and spiritual code, these traditions established and maintained strictly protected areas for centuries. The management system required no state bureaucracy or external funding, drawing its strength instead from the internal cultural and spiritual life of the community. This effective and self-regulating system, however, proved vulnerable to the profound transformations of the colonial and post-colonial eras.

Threats and Transformations (The Crisis)

Despite their historical resilience, these traditional systems of forest management now face a convergence of pressures that threaten their very existence. The cosmological vision that sustained them is being actively undermined by a utilitarian worldview driven by global economic demand, centralized state policy, and the erosion of local belief systems. This section analyzes the economic, political, and social forces driving this crisis.

Economic Pressures and a Utilitarian Worldview

The conflict between the indigenous cosmological model and the colonial economic model is not merely one of policy, but of fundamental philosophy. The utilitarian worldview of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) rendered the very concept of a "sacred" forest meaningless when confronted with material demands. Beginning in the 17th century, the VOC’s immense need for teak for shipbuilding, fuel, and construction established a precedent for treating forests purely as a source of commercial revenue (Boomgaard, 1992).

The inevitable, practical consequence of this worldview was the violation of sacred space. A stark example occurred in 1675 in Jepara, when the VOC felled a ‘sacred’ teak forest despite local reverence. This act was emblematic of the colonial state's role in the "destruction of many a sacred forest," a direct physical manifestation of a philosophy that could not recognize the landscape as a social actor with rights or agency (Boomgaard, 1999).

The Erosion of Social and Spiritual Belief

Perhaps the most insidious threat is the internal weakening of the belief systems themselves. This erosion of the "invisible social fences" was observed by colonial officials as early as the turn of the 20th century. In 1908, forester J.S. Ham remarked that under Dutch influence, the notion of angker was beginning to disappear or weaken among the local population (Boomgaard, 1999).

This represents a generational shift away from a cosmological worldview towards a more secular one, driven by colonial education, economic integration, and the delegitimization of traditional beliefs. As faith in ancestral spirits and the sanctity of the landscape wanes, the taboos that once protected the forests lose their power, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. As these traditional systems face collapse, modern science is, ironically, beginning to recognize and validate their ecological efficacy.

Ecosystem Services and Modern Valuation (The Validation)

As traditional, spiritually-grounded conservation systems face unprecedented threats, modern scientific frameworks are increasingly validating the ecological wisdom embedded within them. This validation bridges the gap between the cosmological worldview and contemporary environmental science, demonstrating that these ancient practices provide tangible ecosystem services vital for both environmental and human well-being. An early, albeit unwitting, scientific affirmation of these traditions emerged from colonial-era concerns over water management.

Beginning in the 1840s, Dutch scientists and officials like Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn and Governor-General Rochussen began to document the link between deforestation on mountain slopes and negative hydrological outcomes, such as a "diminished supply of irrigation water" and an "increased the danger of flooding" (Boomgaard, 1999).

Junghuhn specifically identified three Javanese volcanoes—Merbabu, Sumbing, and Sundoro—as examples where deforestation had led to water scarcity on their higher slopes. The resulting creation of state-led watershed protection forests ( schermbossen ) scientifically affirmed the ecological function of the very upland forests that indigenous communities had long preserved for cosmological reasons, as mountains were often deemed sacred as the "land of the souls."

Key Validated Ecological Metrics

Modern conservation science now measures the precise ecosystem services that these sacred groves provide.

- Biodiversity Sanctuaries: The social taboo against entering angker areas created de facto nature reserves. Because people consistently avoided these sacred places, they "became refuges of wild animals of all descriptions" (Boomgaard, 1999). These groves functioned as critical biodiversity hotspots, providing safe habitat for wildlife in landscapes otherwise being transformed by agriculture.

- Hydrological Regulation: The traditional practice of preserving forests on mountains and hill slopes, rooted in spiritual belief, played a vital role in regulating water cycles. As colonial observers correctly identified, these upland forests were essential for maintaining stable and clean water supplies for the agriculturally productive lowlands, preventing both drought and floods.This scientific validation lends new urgency to the need for understanding and preserving these traditional systems, which offer time-tested models for sustainable human-environment relationships.

Conclusion: Resiliency in Diversity

This examination demonstrates that the traditional Asian vision of the forest, as evidenced in the Indonesian archipelago, is a resilient and sophisticated cosmological model of conservation. It stands in stark contrast to purely utilitarian approaches that reduce nature to a passive object for human exploitation. This analysis reveals an integrated model that seamlessly connects belief with practice to generate demonstrable ecological efficacy.The why is found in the deeply held belief in sacred spaces ( angker ), which provides the moral foundation for conservation. This foundation gives rise to the how —a set of management practices based on social taboos that function as powerful "invisible social fences."

The result is the what : tangible ecological benefits, including the protection of biodiversity and the regulation of vital water resources. For centuries, this integrated system produced sustainable outcomes that modern, state-led models often failed to achieve. Indeed, the historical record of "state-led deforestation" driven by economic demand, such as the VOC's relentless exploitation of teak in colonial Java, offers a powerful cautionary tale (Boomgaard, 1992). The cosmological vision of the forest thus offers more than an alternative paradigm; it serves as a crucial reminder that cultural diversity is an indispensable component of ecological resilience.

References

------

- Boomgaard, P. (1992). Forest Management and Exploitation in Colonial Java, 1677-1897. Forest & Conservation History , 36(1), 4–14.

- Boomgaard, P. (1999). Oriental Nature, its Friends and its Enemies: Conservation of Nature in Late-Colonial Indonesia, 1889–1949. Environment and History , 5, 257–292.

PAPER

Spatial Syntax of the Sacred Ficus

A. Di Paolo

January 12, 2026

PAPER

The Sentient Landscape: An Examination of Asia's Cosmological Vision of the Forest

A. Di Paolo

January 16, 2026

PAPER

An Eco-Dhammic Response: The Realignment of Soteriology and Conservation in Contemporary Thai Buddhism

A. Di Paolo

January 23, 2026