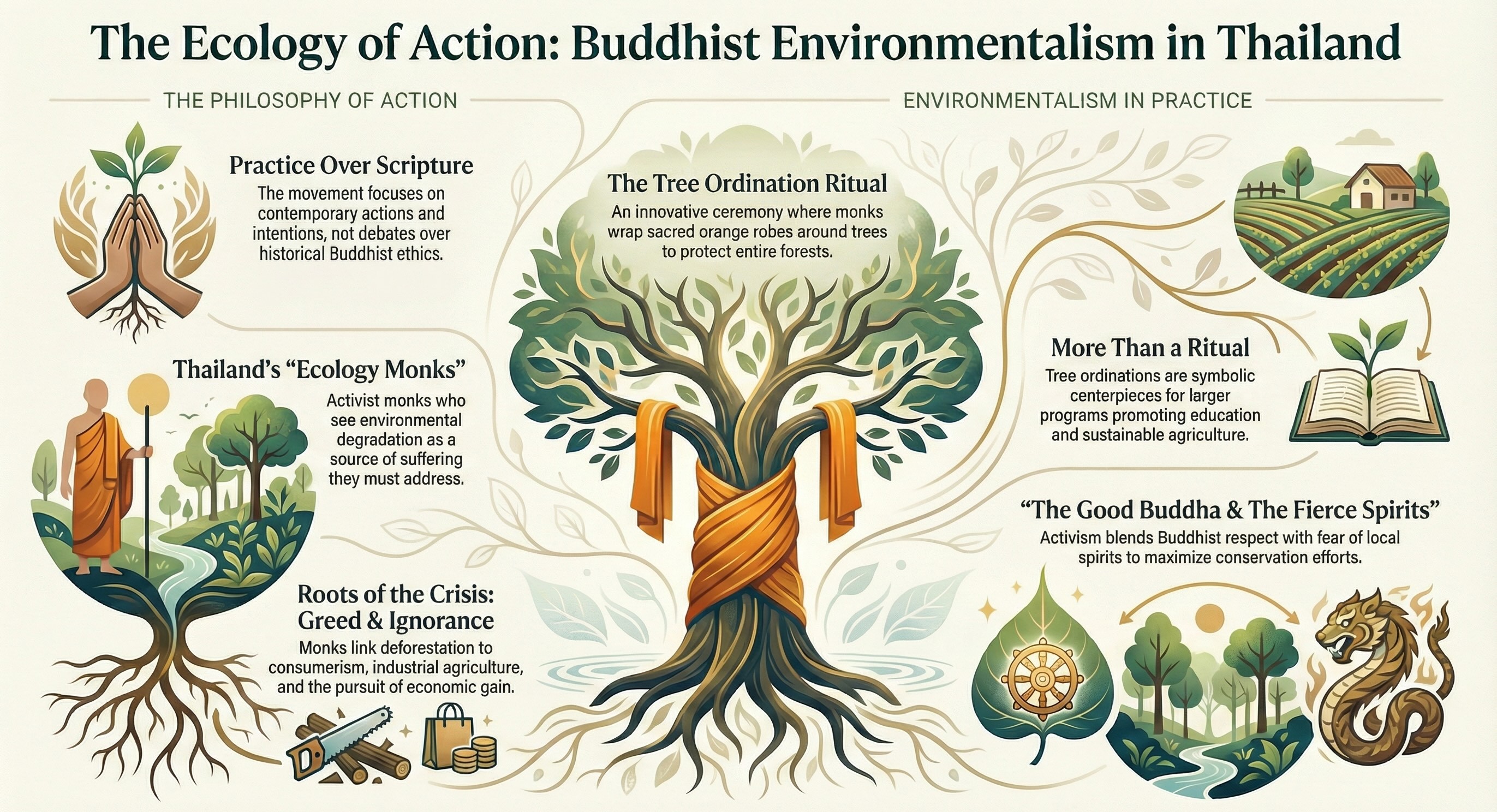

This paper contends that contemporary Thai Buddhism is undergoing a creative and vital reinterpretation of its core doctrines and rituals in direct response to modern socio-environmental crises. Faced with the tangible suffering caused by deforestation and ecological degradation, a cohort of socially engaged monks is realigning the traditional soteriological goal of individual liberation from samsara with the worldly, collective imperative of conservation. This analysis explores the philosophical foundations of this movement, examining how concepts such as dependent co-arising ( paticca-samuppada ) are repurposed as ecological principles. It profiles the key monastic actors, or "ecology monks," who translate these principles into action, viewing the alleviation of suffering "in the here and now" as a foundational practice for ultimate spiritual progress. Furthermore, it investigates the central role of ritual innovation, focusing on the symbolic power of tree ordinations ( buat ton mai ) while also offering a critical evaluation of widespread practices like animal release rituals ( fengsheng ) and their unintended ecological consequences. Ultimately, this paper positions the Thai Buddhist environmental movement as a form of "radical conservatism"—a dynamic effort to apply the fundamental, original teachings of the Buddha to confront contemporary political, economic, and ecological challenges.

Sacred tree Rituals

Ancient Guardians: The Living Heritage of Southeast Asia

M. Rodriguez

January 23, 2026

1. Introduction: The Eco-Dhammic Intersection

The modern environmental crisis, characterised by climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion, has prompted diverse and often profound responses from the world's religious traditions (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology"). As communities grapple with the local manifestations of this global predicament, they increasingly turn to their spiritual frameworks for both solace and guidance.

This paper analyses the specific, practice-based evolution of an environmental ethic within contemporary Thai Buddhism, examining how a small but influential group of monastics has moved beyond traditional roles to address ecological devastation and the human suffering it engenders.This paper argues that contemporary Thai Buddhism is undergoing a significant transformation wherein traditional soteriological goals, primarily focused on the individual’s liberation from the cycle of existence ( samsara ), are being dynamically realigned with the urgent, worldly goal of ecological preservation. This is not an abandonment of core doctrine but a creative reapplication of it, in which conservation is framed as an essential, foundational practice for ultimate soteriological attainment in a world beset by material suffering.

The analysis privileges practice—the tangible actions, rituals, and interpretations of contemporary Buddhists—over abstract textual arguments about whether an inherent environmental ethic exists in early scripture (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology"; Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree"). This methodological choice is grounded in the understanding that religious traditions evolve through their application in new circumstances. The paper therefore adopts what the scholar Donald Swearer terms the "eco-contextualist" approach, which holds that the most effective and authentic Buddhist environmental ethic is one defined by the particular contexts and situations in which it emerges (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology").

To understand these innovative practices, however, requires an examination of the doctrinal re-interpretations that provide their moral and philosophical legitimacy.

3. The Socio-Environmental Crisis

The Buddhist environmental movement arose as a direct and pragmatic response to severe environmental degradation and its devastating impact on rural populations. The suffering caused by deforestation, soil erosion, and water shortages provided the immediate impetus for monks to translate religious principles into social and ecological action.

This section details the specific causes and consequences of this crisis.The rapid loss of Thailand's forest cover, which fell from approximately 53% in 1961 to between 25% and 29% by 1986 according to official figures, was driven by a confluence of economic and political factors. Nongovernmental organisation estimates for the same period placed the figure as low as 15% (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree"). Key drivers include:

- Capitalist Development and Cash-Cropping: Government-led drives for rapid economic development, beginning in the 1960s, promoted a shift away from subsistence agriculture towards consumerism and cash-cropping. Rural people were encouraged to clear forests to plant crops like maize, which often caused significant soil erosion and necessitated further clear-cutting for new agricultural land (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

- The Farmer Debt Cycle: This shift was frequently driven by external pressures. Seed companies and government agricultural banks pushed farmers into cash-cropping, trapping them in a cycle of debt when harvests were insufficient to repay loans. This economic precarity incentivised the expansion of fields into forested land as a desperate measure for survival (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology").

The human and ecological costs of this crisis have been profound. Phrakhru Pitak Nanthakhun, a key figure in the movement, became alarmed by the deforestation, soil erosion, and damaged watersheds around his home village. These environmental changes led directly to the worsening of droughts and a loss of biodiversity, causing his district to become one of the poorest and driest in the province and fuelling high rates of migration to Bangkok (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree"; Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits").

This process of deforestation was also underpinned by a traditional Thai cultural worldview that distinguished between the muang—the civilised, settled, human-centric world—and the paa—the wild, untamed forest inhabited by spirits, dangers, and non-Thai hill peoples. Historically, this dichotomy promoted the "civilising" of the forest by bringing it under cultivation and human control, a perspective that was readily adapted to serve modern development agendas (Darlington, "Environment and Nature in Buddhist Thailand"; Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

This acute crisis of both land and livelihood provoked a new form of socially conscious action from within the monkhood, giving rise to monastic figures who sought to address the suffering they witnessed.

This crumbling edifice stands as a 15th-century architectural homage to the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, India. Constructed during the reign of King Tilokaraj to host the Eighth World Buddhist Council, the Maha Viharn displays a unique fusion of Indian Pala design and Lanna craftsmanship.

3. The Socio-Environmental Crisis

The Buddhist environmental movement arose as a direct and pragmatic response to severe environmental degradation and its devastating impact on rural populations. The suffering caused by deforestation, soil erosion, and water shortages provided the immediate impetus for monks to translate religious principles into social and ecological action.

This section details the specific causes and consequences of this crisis.The rapid loss of Thailand's forest cover, which fell from approximately 53% in 1961 to between 25% and 29% by 1986 according to official figures, was driven by a confluence of economic and political factors. Nongovernmental organisation estimates for the same period placed the figure as low as 15% (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree"). Key drivers include:

- Capitalist Development and Cash-Cropping: Government-led drives for rapid economic development, beginning in the 1960s, promoted a shift away from subsistence agriculture towards consumerism and cash-cropping. Rural people were encouraged to clear forests to plant crops like maize, which often caused significant soil erosion and necessitated further clear-cutting for new agricultural land (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

- The Farmer Debt Cycle: This shift was frequently driven by external pressures. Seed companies and government agricultural banks pushed farmers into cash-cropping, trapping them in a cycle of debt when harvests were insufficient to repay loans. This economic precarity incentivised the expansion of fields into forested land as a desperate measure for survival (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology").

The human and ecological costs of this crisis have been profound. Phrakhru Pitak Nanthakhun, a key figure in the movement, became alarmed by the deforestation, soil erosion, and damaged watersheds around his home village. These environmental changes led directly to the worsening of droughts and a loss of biodiversity, causing his district to become one of the poorest and driest in the province and fuelling high rates of migration to Bangkok (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree"; Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits").

This process of deforestation was also underpinned by a traditional Thai cultural worldview that distinguished between the muang—the civilised, settled, human-centric world—and the paa—the wild, untamed forest inhabited by spirits, dangers, and non-Thai hill peoples. Historically, this dichotomy promoted the "civilising" of the forest by bringing it under cultivation and human control, a perspective that was readily adapted to serve modern development agendas (Darlington, "Environment and Nature in Buddhist Thailand"; Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

This acute crisis of both land and livelihood provoked a new form of socially conscious action from within the monkhood, giving rise to monastic figures who sought to address the suffering they witnessed.

This venerable specimen of Ficus religiosa (sacred fig) at Wat Chet Yot demonstrates a unique intersection of plant physiology and Northern Thai (Lanna) ritual practice. Biologically, the tree has developed a massive, spreading canopy with heavy lateral limbs that are prone to mechanical failure due to their own weight. To mitigate this, the tree is buttressed by a dense array of artificial supports known as mai kham.

Photo by

M. Rodriguez

4. The Monastic Response: The Rise of "Ecology Monks"

In response to the suffering caused by environmental degradation, a small but influential group of "ecology monks" (phra nak anuraksa) emerged in Thailand. These monks moved beyond the traditionally more circumscribed roles of the Sangha to engage in direct social and environmental action, arguing that it was their duty as Buddhists to relieve suffering in all its forms, including that which is ecologically derived (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

Several monastic figures have been central to the development of this movement, each employing distinct strategies to achieve their conservation goals:

- Phrakhru Pitak Nanthakhun: As a leading figure in Nan Province, Phrakhru Pitak is known for his pragmatic and holistic approach. He co-founded the "Hak Mueang Nan" (Love Nan Province) group, a coalition of NGOs, to support his conservation projects. His "Good Buddha and Fierce Spirits" strategy is particularly noteworthy for its skilful integration of traditional spirit beliefs with Buddhist rituals. By establishing shrines for guardian spirits alongside Buddha images in protected forests, he leverages both the respect villagers have for the Buddha and their fear of the spirits to ensure compliance with conservation rules (Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits").

- Phra Prajak Khuttajitto: Phra Prajak represents a more radical and controversial wing of the movement. He was known for his explicit political actions and overt challenges to government-led relocation programmes in the northeast, which aimed to displace villagers to make way for eucalyptus plantations. His direct activism and willingness to confront state power led to his arrest on two occasions, highlighting the political risks inherent in Buddhist environmentalism (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology"; Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits").

- Other Monastic Innovators: The movement has been advanced by the contributions of many other monks. Phrakhru Manas Natheephitak of Phayao Province is credited with performing the first tree ordination specifically for forest conservation in 1988. He based the ceremony on the traditional northern Thai ritual to sanctify a Buddha image (buat phraphuttha rup), during which tree saplings were placed at the statue's base and sanctified alongside it. Villagers began calling these saplings "ordained trees," giving the new conservation rite its name (Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits"). His disciple, Phra Somkit, was later recognised for his own environmental work with a 'Green World' award, indicating the growing acceptance of such activities (Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits").

These monks' most visible and potent tools were their innovative adaptations of traditional Buddhist rituals, which became the public face of their movement and the primary medium for their theological message.

5. Ritual Innovation and Critical Analysis

Ritual functions as a core strategic tool for the Buddhist ecology movement. Ecology monks creatively adapted traditional ceremonies not merely to sanctify nature but to achieve tangible social and political goals: building community commitment, raising national awareness, and creating a powerful moral and symbolic challenge to prevailing political and economic norms that drive environmental destruction.

The tree ordination (buat ton mai) has become the flagship ritual of Thai Buddhist environmentalism. The ceremony involves the symbolic ordination of large, important trees by wrapping them in the saffron robes of a monk. This act is accompanied by chanting, sermons, and the establishment of community rules forbidding the cutting of any trees or harming of wildlife within the sanctified forest (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

This ritual serves as a direct ideological counter to the traditional muang/paa worldview that promoted the "civilising" of the forest. By conferring upon a tree a status symbolically equivalent to a member of the monastic Sangha, the ceremony re-sanctifies the paa, framing it not as a wild realm to be conquered and cultivated, but as a sacred entity deserving of reverence and protection. What began in 1988 as a radical act of protest has evolved into a mainstream, nationally recognised practice, so much so that it is sometimes co-opted by state and corporate actors, threatening to dilute its original counter-hegemonic power (Darlington, "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits").

While the tree ordination represents a conscious environmental adaptation, the traditional animal release ritual provides a cautionary example of a well-intentioned practice with severe, unintended negative consequences. Though rooted in the core values of compassion and merit-making, its modern application often demonstrates a profound lack of ecological awareness (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology").

In response to growing criticism from scientists and conservationists, innovative Buddhist leaders have sought to reform the practice. Venerable Benkong Shi of the Grace Gratitude Buddhist Temple in Manhattan, New York, for example, initiated a "Compassionate Release" programme. This adapted ritual partners with certified wildlife rehabilitators to ensure that the animals released are native species being returned to suitable habitats in an ecologically sound manner. This model demonstrates how a traditional practice can be integrated with scientific ecological principles to achieve both spiritual and environmental goals (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology").

The diversity of these practices has prompted significant discussion among scholars seeking to understand and categorise the various forms of Buddhist environmentalism.

6. Scholarly Perspectives and Typologies

The rise of the Buddhist ecology movement has been situated within a broader academic discourse. Scholars have debated whether a genuine environmental ethic is inherent in Buddhist scripture or is a modern construction, and they have developed typologies to categorise the different approaches observed in practice as Buddhism confronts the contemporary environmental crisis.

A central academic debate contrasts two primary approaches. The "textual approach" involves a close examination of early scriptures like the Pali canon to determine if an authentic environmental ethic exists within foundational Buddhist thought. In contrast, the "practice approach," which Darlington explicitly favours, focuses on the actions, interpretations, and intentions of contemporary Buddhists as they respond to modern crises.

This latter approach prioritises the living, evolving nature of the tradition over scriptural literalism (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology"; Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree").

To help navigate these diverse perspectives, scholar Donald Swearer developed a five-category typology for assessing Buddhist environmentalism:

- Eco-apologist: This position holds that an environmental ethic extends naturally and inherently from the Buddhist worldview.

- Eco-critic: This position argues that the traditional Buddhist worldview, with its focus on human liberation from samsara, does not harmonise with a modern environmental ethic.

- Eco-constructivist: This position maintains that while a Buddhist environmental ethic is not inherent, one can be convincingly constructed from doctrinal tenets and texts.

- Eco-ethicist: This position argues that a viable Buddhist environmental ethic should be evaluated primarily in terms of Buddhist ethics rather than being inferred from the broader worldview.

- Eco-contextualist: This position, which aligns with the approach of this paper, holds that the most effective and authentic Buddhist environmental ethic is defined by particular contexts and specific situations. (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology")

These movements, understood through an eco-contextualist lens, represent not a deviation from tradition but a unique fusion of tradition and innovation, culminating in a new form of engaged practice.

7. Conclusion: A New Dharma of Radical Conservatism

This paper has demonstrated how Thai ecology monks, driven by the direct experience of suffering caused by the nation’s socio-environmental crisis, have forged a powerful response grounded in the creative reinterpretation of core Buddhist doctrines. They have repurposed philosophical concepts of interdependence as ecological imperatives and transformed traditional rituals into potent tools for conservation and social critique. In so doing, they have re-contextualised the path to liberation, arguing that relieving suffering "in the here and now" is a necessary first step toward later spiritual progress, thereby linking the philosophical foundations of their faith to the practical, political, and ecological struggles of rural communities.

The Thai Buddhist environmental movement can be best understood as a form of "radical conservatism" (Darlington, "The Ordination of a Tree"). The movement is conservative in that it does not advocate for a new form of Buddhism; rather, its proponents argue they are returning to the original, fundamental teachings of the Buddha concerning compassion and the relief of suffering. It is radical in its application of these core teachings to confront contemporary socio-economic and ecological problems in creative, politically engaged, and sometimes confrontational ways.

This approach challenges government development policies and the consumerism that underpins them, thereby moving Buddhism firmly into the realm of social and political action. The subsequent co-option of their flagship ritual, the tree ordination, by state actors represents a profound test of this model: while it signifies the movement's success in making conservation mainstream (its conservative appeal), it also risks diluting the ritual's power to challenge state development policies (its radical edge).

The efforts of Thailand's ecology monks exemplify the vitality and adaptability of a "living tradition" (Darlington, "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology"). By realigning soteriological aims with ecological realities, they demonstrate how ancient wisdom can be marshalled to address the most pressing crises of the modern world, offering a compelling model of spiritually grounded environmental action.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

8. Bibliography

- Darlington, Susan M. "Contemporary Buddhism and Ecology." In The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, edited by Michael Jerryson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Darlington, Susan M. "Environment and Nature in Buddhist Thailand: Spirit(s) of Conservation." In Nature Across Cultures, edited by Helaine Selin. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, 2014.

- Darlington, Susan M. "The Good Buddha and the Fierce Spirits: Protecting the Northern Thai Forest." Contemporary Buddhism 8, no. 2 (November 2007): 169–85.

- Darlington, Susan M. "The Ordination of a Tree: The Buddhist Ecology Movement in Thailand." Ethnology 37, no. 1 (Winter, 1998): 1–15.