Beneath the sprawling, labyrinthine canopy of an ancient Waringin, time loses its linear momentum, congealing into a dense, physical stasis. To the uninitiated observer, this specimen merely represents a member of the genus Ficus; yet, the Balinese recognise it as a sentient, living monument—a "bio-cultural artifact" that pulses at the very core of the island’s identity. One’s first encounter triggers a profound sensory response: the humid, cloying scent of burning incense rising from the buttress roots; the gnarled, obsidian-like texture of bark that has witnessed centuries of transition; and the hypnotic interplay of dappled light and profound shadow within its interior. This tree functions not as a passive landscape element but as a vital bridge between the physical and the metaphysical. Yet, beneath this atmospheric mystique, the rigorous botanical reality of Ficus benjamina and Ficus benghalensis provides the architectural framework for this complex spiritual iconography.

Sacred Tree Rituals

Discover how Ficus trees bridge the physical and spiritual worlds in Balinese tradition, serving as bio-cultural monuments that anchor island communities

A. Di Paolo

February 5, 2026

Botanical Architecture and Ecological Symbolism

The physical traits of the Waringin—known locally as the grodha agung—transcend biological curiosity to form the structural foundation of its sacred status. Every morphological feature operates as a visual signifier within Balinese cosmology.

• The Hemiepiphyte Life Cycle: The Waringin begins its life as a "strangler." As a hemiepiphyte, it germinates high in the canopy of a host tree, eventually sending aerial roots downward to find the soil. Once these roots anchor, they undergo "anastomosis"—a process where the roots fuse and graft together, eventually enveloping and suffocating the host. The Balinese interpret this biological "rooting" as a metaphor for how spiritual traditions must entwine with and eventually dominate the physical realm.

• Aerial Roots as Cosmological Conduits: The extensive hanging roots generate a palpable sense of tenget (sacred power). These vertical structures articulate the connection between the Suah (upper world) and Bhur (lower world), acting as conduits that ground celestial energy into the terrestrial soil.

• The Canopy and Pengayoman: The dense, protective shade of the Waringin creates a cooling microclimate known as pengayoman. This biological shelter provides more than relief from the tropical sun; it symbolises divine guardianship. The same canopy that protects human bodies also marks a ritually charged zone where the community offers prayers to resident forces.

• Longevity and Pitra Yadnya: The tree’s capacity to live for centuries transforms the massive trunk into an axis mundi. This endurance links the tree directly to pitra yadnya (rites for the dead). In Balinese ancestral rites, the grodha agung serves as a symbol of purification and ancestral ascent, facilitating the spirit’s journey toward unity with the divine.

These botanical signifiers transition seamlessly into the "signified" meanings of the Balinese universe, where biology and belief coalesce into a single, unified system of sacredness.

The Waringin in the Village Mise-en-Scène

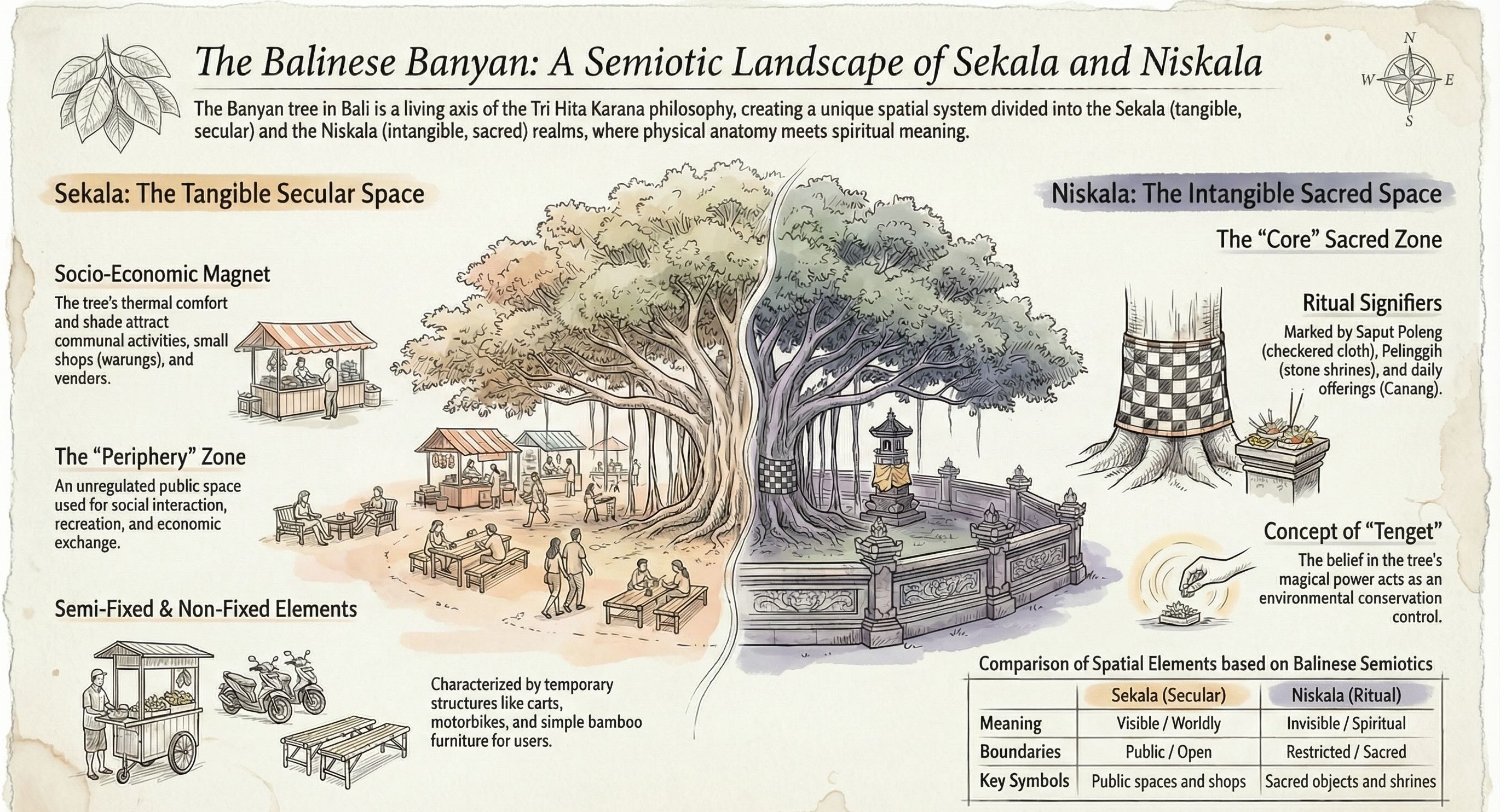

The Waringin acts as the visual and spiritual anchor for Balinese spatial organisation, materialising the principle of Tri Hita Karana—the harmony between humans, nature, and the divine. Its placement follows a deliberate "spatial syntax" that defines the village mise-en-scène.

These trees typically form a "standard cluster" at the community’s heart, positioned near the Pura (temple), the Wantilan (assembly hall), and the marketplace.

This placement allows the tree to facilitate the interaction between "fixed elements" (the permanent shrines and the tree itself) and "non-fixed elements" (the fluid movement of vendors, vehicles, and social users). While the tree’s shade serves the secular functions of trade and gossip, its proximity to crossroads and temple gates ensures that every social interaction occurs within the literal shadow of the divine. This arrangement reinforces the tree’s role as a spatial signifier of cosmological balance.

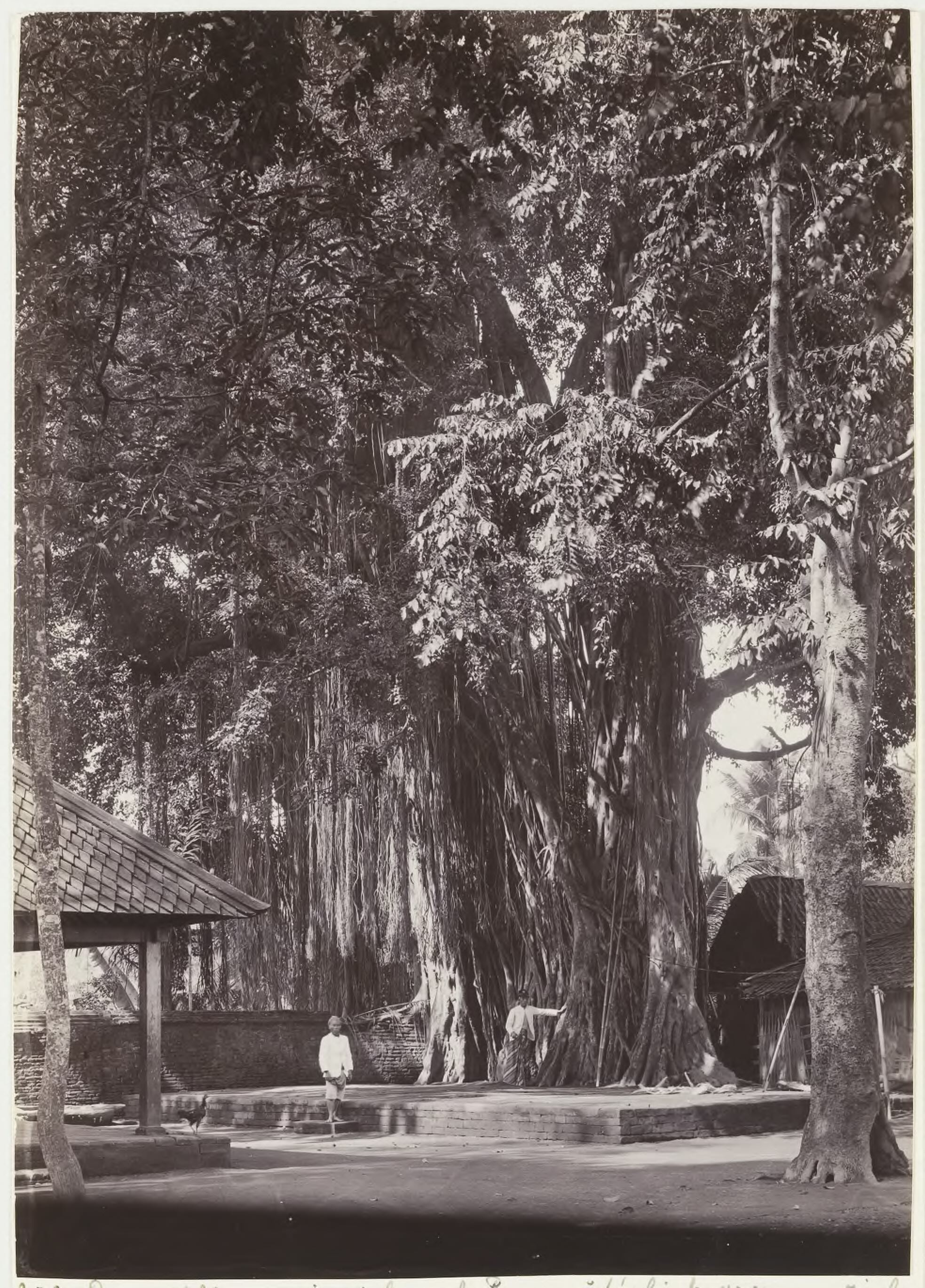

Arboreal Majesty: The Giant Banyan of Pasar Gede, Yogyakarta, 1896 - Source: Leiden University Library

The Waringin in the Village Mise-en-Scène

The Waringin acts as the visual and spiritual anchor for Balinese spatial organisation, materialising the principle of Tri Hita Karana—the harmony between humans, nature, and the divine. Its placement follows a deliberate "spatial syntax" that defines the village mise-en-scène.

These trees typically form a "standard cluster" at the community’s heart, positioned near the Pura (temple), the Wantilan (assembly hall), and the marketplace.

This placement allows the tree to facilitate the interaction between "fixed elements" (the permanent shrines and the tree itself) and "non-fixed elements" (the fluid movement of vendors, vehicles, and social users). While the tree’s shade serves the secular functions of trade and gossip, its proximity to crossroads and temple gates ensures that every social interaction occurs within the literal shadow of the divine. This arrangement reinforces the tree’s role as a spatial signifier of cosmological balance.

Sacred Sentinel: The Monumental Waringin of Gianyar, Bali (c. 1920) - Source: Leiden University Library

Case Study: The Artist's Lens and the Construction of Mystique

While indigenous semiotics root the Waringin in ancient tradition, external observers significantly constructed the island’s modern "mystique." The 1952 expedition of four pioneering Singapore artists—Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi, Chen Chong Swee, and Cheong Soo Pieng—marks a milestone in Singapore’s art history and the construction of the Balinese image.

The 1952 Trip: Documenting the Niskala

Armed with newly purchased Rolleiflex f/3.5 cameras, the quartet embarked on a seven-week journey to capture what they perceived as an "untouched Eden." For decades, the primary record of this trip remained lost, until researcher Gretchen Liu discovered a forgotten Bata shoebox containing approximately 1,000 negatives. These photographs document the artists’ search for inspiration at sites like Puri Agung Karangasem, where Liu Kang famously captured a group portrait in a large mirror on the Dutch-style verandah.

The Colonial Fantasy vs. Indigenous Reality

The Singapore artists did not operate in a vacuum; they responded to a century of Dutch colonial promotion. Since 1914, travel brochures had mythologised the "Gem of the Lesser Sunda Isles," promoting a "Colonial Fantasy" of a romanticised paradise. The Singapore quartet’s subsequent 1953 exhibition helped burnish this image in the regional imagination. However, their sketches and Rolleiflex photographs often prioritised the Sekala (the visible beauty of rice terraces and "exotic" women) over the complex, often brutal realities of Dutch colonisation and the mass ritual suicides (puputan) that preceded the tourist era. These artists attempted to document the Niskala (the invisible spirit) through a modern lens, bridging the gap between indigenous sacredness and Western artistic modernism.

Conclusion: Conservation of the Living Heritage

The resilience of the Waringin provides an enduring testament to the principles of Tri Hita Karana. In a modernising world, the protection of these trees represents much more than environmentalism; it constitutes the preservation of Balinese heritage itself. These trees serve as critical "biocultural nodes" that maintain the integrity of the Southeast Asian landscape.

Safeguarding the Waringin ensures that the link between Sekala and Niskala remains intact. To lose the tree is to lose the spatial and spiritual anchor of the community. Therefore, maintaining the "bio-cultural" integrity of these living monuments is a strategic necessity. The grodha agung remains a silent witness, providing pengayoman to the Balinese people across generations and ensuring that the bridge between nature and the divine remains standing.

Bibliography

--------

- Wijaya, I Kadek Merta. (2019). "The Semiotics of Banyan Tree Spaces in Denpasar, Bali." LivaS: International Journal on Livable Space, Vol. 04, No. 2, pp. 48-59. This text operationalizes Saussurean semiotics to investigate the dichotomy between sekala (tangible) and niskala (intangible) spaces.

- Sunnland, Tai. (2013). A River Runs Through It: Re-Imagining Kuta's Neglected River. Doctorate Project, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. This dissertation applies the cosmological framework of tri hita karana and theories of landscape urbanism to reclaim neglected ecological systems in Kuta.

- Liu, Gretchen, Nadia Ramli, Goh Yu Mei, and Low Sze Wee. (2025). BiblioAsia, Vol. 21, Issue 01, National Library Board Singapore. This collection includes specific ethnographic documentation regarding the 1952 artistic expedition to Bali and the subsequent construction of the island’s "mystique" as an untouched Eden.

- Ferrari, Fabrizio M., and Thomas W.P. Dähnhardt (Eds.). (2016). Roots of Wisdom, Branches of Devotion: Plant Life in South Asian Traditions. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing. This volume provides a theoretical analysis of botanical lore in South Asian religious traditions, including the hagiographical significance of the kalpavr̥kṣa (wish-fulfilling tree) and the audumbarī rite.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt. (2015). "Sanctity of the Banyan Tree." The Hindu Portal. This article discusses the symbolic role of the Banyan tree as a "hermit among trees," representing spiritual permanence and immortality within Hindu thought.

- Pranajaya, I Kadek, Ngakan Ketut Acwin Dwijendra, I Putu Oka Swiranatha, and Ni Made Emmi Nutrisia Dewi. (2025). "The Significance of Cultural, Religious, and Sustainability Symbols in the Revitalization of Architects and Temple Interiors at Luhur Batukau Temple in Bali." Civil Engineering and Architecture, 13(3A), pp. 2601-2619. This study analyzes the cultural acculturation and symbolic meanings of the tripartite structure in temple architecture.

- Picard, Michel (Ed.). (2017). The Appropriation of Religion in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. This text deconstructs the category of "religion" as a normative Western concept, investigating the process of "religionization" and the localization of world religions in societies like Bali, Burma, and Cambodia.

- Anonymous Research Synthesis. (n.d.). "Visual Semiotics of the Beringin (Banyan tree) as a Sacred Entity in Bali.". This document provides an analytical synthesis of the constituent visual elements of the Banyan tree—such as aerial roots and dense canopies—in relation to their function as spatial signifiers.