Reading the news about our planet often brings a sense of low-grade anxiety. The crisis feels immense, and proposed solutions seem disconnected from our daily lives. We hear about large government policies that feel distant, while small individual actions, though important, can seem inadequate. We find ourselves caught between systems too big to influence and actions too small to matter. But what if powerful environmental wisdom lies not in modern science but in ancient traditions and the experiences of communities that have maintained a sacred relationship with their land? These are not relics of the past but resilient strategies for living within our planet's limits. This article explores five counter-intuitive truths from Southeast Asia that challenge our assumptions about protecting the natural world, offering lessons that are both ancient and urgently relevant.

CONSERVATION

Reconciling Modern Ecology with the Sacred and Sustainable Wisdom of Ancient Forest Traditions

A. Di Paolo

March 15, 2022

1. Some of the World's Best Nature Preserves Are Cemeteries.

It’s a startling idea, but some of the most effective and resilient nature preserves on Earth are not national parks, but graveyards. Across the globe, burial sites and other sacred groves often function as unintended biodiversity hotspots.

Often located outside of settlements and protected by walls or fences, these sites are physically and culturally insulated from disturbance. Because these areas are respected and left untouched, they become vital refuges for rich and diverse vegetation.

This phenomenon isn't isolated. Researchers have documented the crucial role of graveyards in conserving native plant life in countries as varied as Morocco, Ethiopia, China, Italy, and Pakistan. These sites act as living seed banks and remnant patches of original ecosystems in otherwise developed landscapes.

One study highlighted a particularly beautiful example of this relationship, finding that many ancient graveyards in Turkey have become critical sanctuaries for native orchids, protecting them from the threat of over-harvesting.

The Sanctuary of Bunut Bolong Stone shrines nestle beneath a majestic banyan at the Bunut Bolong temple in Bali. Functioning as unintentional nature preserves, such sacred sites effectively protect native biodiversity through deep spiritual reverence and fear of the divine.

Photo by

A. Di Paolo

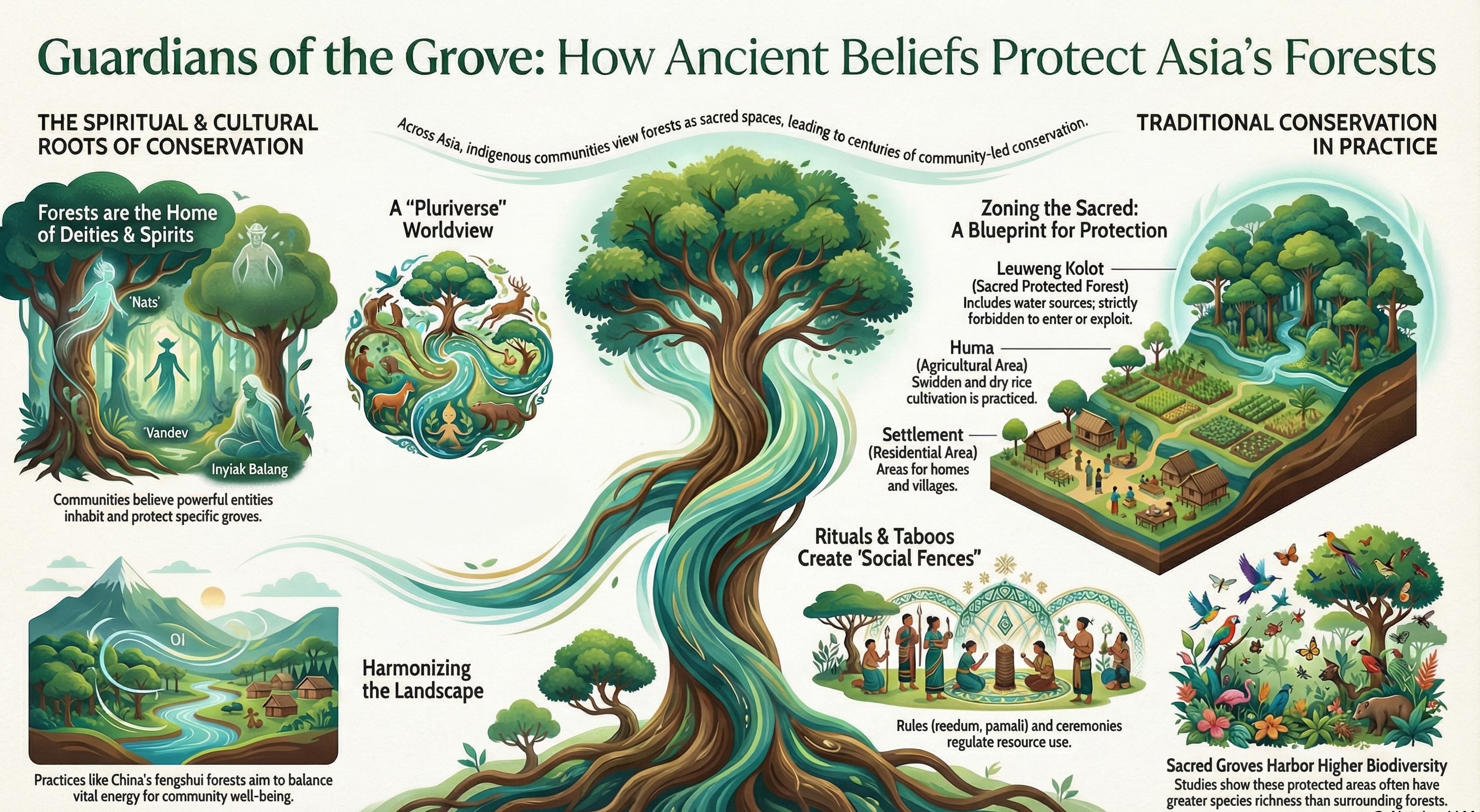

2. Feng Shui Isn't Just for Your Living Room—It's for Entire Ecosystems.

In the West, feng shui is popularly known as a set of principles for arranging furniture to promote harmony and good fortune within the home. But in southern China, this tradition has been applied on a much grander scale as a powerful tool for ecosystem management.

For centuries, communities have designed their landscapes around fengshui forests ( fengshuilin ).The core principle is that the flow of qi (vital energy) through a village can be optimized by strategically protecting ancient forests and planting new trees.

This practice, rooted in cosmology, yields profound ecological benefits. These strategically placed forests conserve precious soil and water resources, which in turn strengthens the resilience of the entire agricultural system, particularly subtropical wet rice farming.

It reveals a worldview where the forest, the village, and the farm are not separate units, but a single, interconnected, and living system."Ancient trees and forests are living exempla of resilience in the face of social, economic, and political change.

This chapter explains the deep association between landscape integrity and community health and well-being, a dynamic relationship between land and people that constitutes lineage socio-ecological systems, or “wind-water polities.”

The term "wind-water polities" captures the sophistication of this worldview. It describes a community where political and social structures, ecological health, and cosmological beliefs are inseparable. These are "lineage socio-ecological systems," managed as a single, integrated entity across generations. This is not just interior design for the landscape; it is a complete model of governance that binds the fate of the people to the health of their environment.

The Sanctuary of Bunut Bolong Stone shrines nestle beneath a majestic banyan at the Bunut Bolong temple in Bali. Functioning as unintentional nature preserves, such sacred sites effectively protect native biodiversity through deep spiritual reverence and fear of the divine.

Photo by

A. Di Paolo

3. The Most Effective Fences Are Invisible.

How can a forest be protected for generations without walls, fences, or legal statutes? The answer lies in a concept that modern ecologists have termed the "invisible social fence."

The protection of many of Asia's sacred groves relies not on physical barriers, but on a powerful, shared set of cultural taboos and beliefs.In these systems, the local deity is viewed as having ultimate authority over the forest, acting as a "moralizing entity."

The plants and animals within the grove are protected because community members share a deep-seated fear of transgressing taboos and provoking the deity's wrath, unleashing calamity, including illness, crop failure, or unpredictable weather, on the village.

This collective belief system creates a powerful social boundary that governs community behavior far more effectively than any physical fence ever could. It is a form of governance rooted in cosmology, where ecological rules are enforced by divine sanction.

"The protection given to vegetation and animals in the sacred forest derives from fear of transgressing the taboos and consequently feeling the wrath of the deities."

The Invisible Fence of Poleng Draped in traditional Saput Poleng cloth, this sacred tree is guarded by an 'invisible fence' of cultural taboo. The black-and-white fabric symbolises the balance of spirits, protecting the tree through shared community values rather than physical barriers.

Photo by

A. Di Paolo

4. Some "Sacred" Forests Are Actually Strategic Hunting Grounds.

The term "sacred" often conjures images of pristine, untouched nature—places set apart from all human use. However, research among the Iban people of West Kalimantan, Indonesia, reveals a more complex and pragmatic relationship with the landscape.

While the Iban designate certain patches of forest as sacred, these areas are not entirely off-limits.In a surprising finding, data showed that hunters focus their efforts disproportionately on sacred forests, even though these areas represent only 2% of the total land they hunt.

The reason is entirely practical: the sacred forests contain a high concentration of fruit trees that attract animals, making them ideal and predictable locations for hunting.However, the relationship is more complex than it first appears. When measured not by hunting effort but by the total weight of prey captured, other areas like old fallow lands and tree reserves provided the vast majority (85%) of the community's game.

This reveals a sophisticated, managed relationship where sacredness is integrated into subsistence, not separated from it. The sacred grove serves not as the community's primary pantry, but as a strategic and predictable location for encountering game, while the wider, managed landscape provides the bulk of their sustenance.

5. Ancient Cultures Scheduled a "Day Off" for the Earth.

The modern concept of a weekend is a social invention designed to give workers a rest. But what if we applied the same logic to the land itself? Among the Mahadev Koli people in the Bhimashankar region of India, a traditional practice called moda does exactly that. Moda is a designated day each week when all agricultural activities are forbidden.

Associated with a village deity—often Vandev on Sundays or the goddess Kalamjai on Tuesdays—it serves as a mandatory, community-wide day of rest for the fields.

This ecological sabbath is a culturally enforced mechanism that prevents over-exploitation and allows the land a regular period of recovery.As one villager explained it, the concept is simple and powerful:

"You know, the government has specifc holidays such as Saturday, Sunday for all of India; similarly moda for us is a holiday for the whole village. Our moda is ‘fx’ on Sunday and one does not work in felds that day."

Conclusion: The Wisdom We Can't Afford to Lose

These examples reveal that sacred groves are not mere "biocultural relicts" of a bygone era. They are dynamic, living systems of knowledge that demonstrate a profound understanding of the interconnectedness between ecology, community, and cosmology.

These traditions have proven their resilience, often outliving the specific political or social contexts in which they first arose.They remind us that the foundation of a sustainable relationship with our planet may not lie in new technologies alone. It also lies in a different way of seeing—one that recognizes the landscape as a living partner rather than a resource to be exploited.

As we face the challenges of the Anthropocene, what other crucial wisdom for a sustainable future lies hidden not in a lab, but in ancient tradition?

Enjoyed reading this post? Share it with your network!